Ambedkar ‘s Perspective on Restructuring Indian Nation in the context of Dalit Question

Sukhadeo Thorat*

Introduction

The Caste System in its classical form is an unique institution of social governance of the Hindu society. It is based on some specific principles and rules which make it an unique one. Foremost of them is that it involve a division of persons in various social groups called castes The division is created and maintained through institution of endogamy. The duties and the rights, (civil, cultural/religious, political and economic) are assigned to each of these castes by birth in advanced but in an unequal manner . The duties and rights are thus pre-determined by birth in to the specific caste and are hereditary ,not subject to change by deeds of the individuals . The social position or standing of each caste is hierarchically arranged , in the sense that the rights gets reduced in descending order, that is , from the Brahmin( who are located at the top of hierarchy) to the untouchable ,who are placed at the bottom of the caste hierarchy .The caste are hierarchically arranged in a manner that they are interlinked with each other such that rights and privileges of the high castes become the disabilities of the lower castes .In this sense caste does not exist in single number but only in plural , and interlinked (or made interdependent) with each in an unequal measure of relationship. Therefore one has to look at castes as “system” and not caste as single entity in isolation. Another distinguish feature of this system is that it laid down a systematic machanism for enforcement in the form of social and economic ostracism involving penalties and punishments against the violation of the system in practice. But above all the system is sanctified and supported, directly or indirectly by the philosophical elements in Hindu religion. Therefore for generality of Hindus the caste system is religiously sanctified institution to be practice as system of divine creation and matter of religious faith. It is this religious foundation and sanctity, which provide enduring strength and stubbiness to the institution of caste (Lal Deepak, 1984, Ambedkar 1936 and 1987 )

Thus the caste system is essentially based on the divine principle of inequality encompassing all spheres (civil, cultural, religious, economic and political) of social relations. In its practical consequence it has lead to immense inequality between the caste groups. But the real burden of the system has fallen on the untouchables in so far as they did not have any rights ,civil ,religious or economic. The untouchables not only suffered from lack of any rights of livelihood but they are also excluded and isolated through the institution of untouchability and un approachability and residential segregation and physical separation . So the “Isolation and exclusion” is the unique feature from which only untouchables suffer. The lack of any rights, coupled with exclusion, isolation and discrimination led to highest degree of social and economic deprivation among the untouchables .

How to reform the Hindu social order and solve the problem of untouchable is the problem with which Ambedkar was pre-occupied and devoted most of his intellectual, social and political efforts during the period between early 1920 to mid 1950. Ambedkar began social and political activities around early 1920’s . The early 1920s is a period which is marked by some crucial development. It is necessary to mention them here because, it is during this period that important political and social organizations had emerged.And it is through encounters and interaction with various ideological stands that Ambedkar’s alternative ideological paradigm had been developed. Gandhiji emerged on the political scene in the early 1920 and with this also emerged “Gandhism” which in tern had a powerful influence on the perspective on the question of dalit particularly by the congress . The communist party was established in 1920 in Kanpur and with this a formal Indian Communist Movement began with its base in “communist ideology”. Similarly, the democratic socialists thoughts and groups associated with few of its variants also emerged during this period. The Arya Samaj Movement though started earlier become very active in 1930s particularly in northern India. At the other ideological extreme RSS was formed in 1925 in Maharashtra , the state where Ambedkar come from. This is also period during which non Brahnism movement was quite active .And this is also the period of an active dalit movement initiated by Ambedkar. . It is necessary to recognize that all these movements had the issue of untouchable on their agenda in one way or other. Therefore Ambedkar came in constant contact with most of them and fairly closely with two of them namely Gandhism and Marxism. The interaction and experience was really facilitated by the fact that the center stage of these movements was western India – more particularly the Maharashtra state and with in Maharashtra, a city of Bombay – the state and city where Ambedkar came from. Ambedkar not only interacted with Gandhism, Marxist and the socialists and backward caste movements but in the initial years was associated with some of them. And it is through this interaction and experience that Ambedkar’s alternative ideological position was developed in the latter years.ureing.

In this context this paper focuses on some selected issues on the question of reform of Hindu society .Firstly we trace the encounter of Ambedkar with the alternative ideological paradigms on the issue of restructuring of Hindu social order .We concentrated only on two of them namely Gandhism and Marxism , and highlight the differences (or similarities) between them .Secondly we examine as to how the limitation of these two ideological approaches ( in Ambedkar’s view) in explaining and solving the problem of untouchables induce Ambedkar to search for an alternative perspective which later on came to be known as “Ambedkarism” (Gail 1994).Thirdly we study the influence of Ambedkar ‘s perspective on the evolution of the Indian policy toward the dalits and finally trace the changes in their social and economic condition since independence in 1947.

Gandhism and Dalits – Ambedkar ‘s Response

Ambedkar and Gandhiji began social and political activities for eradication of untouchability almost in same period i.e. in the early 1920’s and infact also worked together for short time However, over a soon Ambedkar could not find much common ground for cooperation and collaboration and initiated activities through his own platform . It is therefore necessary to state the difference in the position of Gandhi and Ambedkar on the question of restructuring of Hindu social order . This is necessary because Gandhism may have become a less powerful force in several sphere but as a ideological solution to the problem of untouchable continue to have significant influence and guiding force for several organizations like Harijan Sevak Sangh. The only common ground for Gandhiji and Ambedkar is their concern for the problem of untouchability – both worked for its eradication. But their explanation and solution differs significantly. In this context at least three important differences about Gandhiji’s position needs to be understood. Because more often that not Gandhiji’s view on untouchability and caste are interpreted in an manner which are in contravene to the writings of Gandhiji himself.

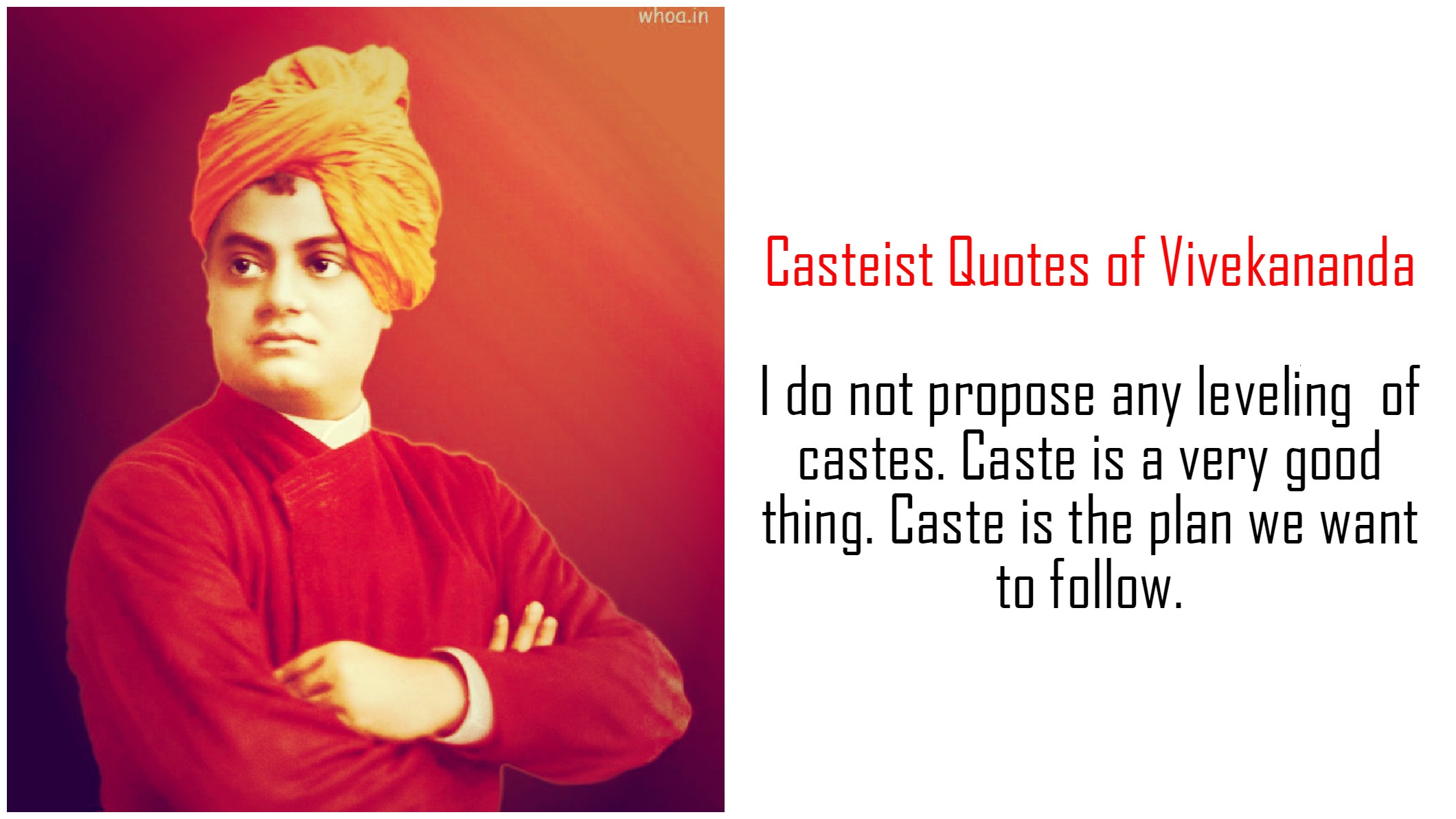

Firstly, Gandhiji opposed the practice of untouchability but believed that untouchability has no serious connection with Hindu social organization namely the caste system.

Secondly, till 1946 Gandhiji supported caste system. . Ambedkar quote Gandhiji on this issue :

“I believe that if Hindu society has been able to stand because it is founded on the caste system. Caste has a ready made means for spreading primary education, caste has a political basis. Caste can perform judicial function. I believe that inter dining or inter-marriages are not necessary for promoting national unity. The caste system cannot be said to be bad because it does not allow inter dining or inter-marriage between different caste. To destroy caste system and adopt Western European Social System means that Hindu must give up principle of hereditary occupation which is the soul of caste system. The caste system is a natural order of society. This being my views I am opposed to all those who are out to destroy the caste system.( Ambedkar 1946)

In 1925 Gandhiji became critical of caste system and observed.

“I gave support to caste system because it stands for restraint. But at present caste does not mean restraint,it means limitations.Restraint is glories and helps to achieve freedom. But limitation is like a chain .Its binds.There is nothing comandable in castes as they exist today.They are contrary to the tenets of the shatras.The number of castes is infinite and there is bar against intermarriage .This is not a condition of elevation. It is a state of fall.”

Gandhiji suggested an alternative to the caste system.

“The best remedy is that small castes should fuse themselves into big caste. There should be four such big castes so that we may reproduce the old system of four varnas.

The varna system suggested by Gandhiji is however, different from that of Arya Samaj or Geeta .The concept of Varna system of Geeta and Arya Samaj simply label the people in four Verna depending on the basis of occupation but there is freedom for individual to move from one varna to another if the occupation is change.So the process of learning ( or the taking of occupation of other varna) is open and free.Gandhiji ‘s concept of the varna system is different ,in the sense that in makes the learning process open to all varnas but it does not allow them to use acquired skill and knowledge for earning his living other than the occupation assigned to varna . The principle of hereditary occupation is the basis of new varna system of Gandhiji.So Gandhiji ‘s concept of varna is closed to the traditional concept of caste system .It only make small concession in so far as it allowed every varna the access to education or learning but it restrict the use of knowledge for taking the occupation of other that your own varna.So the untouchable may have access to education and skill formation but they should continue to carry their traditional or hereditary occupation namely of serving other Varna. Thus the alternative concept of Varna prescripted by Gandhiji is essentially is not different from that of caste system of Manu.

Thirdly, Gandhiji denies any connection of caste system with Hindu religious ideology.As we shall see later Ambedkar differs with Gandhiji on each of these points namely, inter-connection of untouchability with caste system and of both with Hindu religious ideology and Gandhiji’s modified varna system as a ideal form of social organization.Therefore, there has been a much less common ground on the question of restructuring of Hindu social order and hence the question of dalit.It may also be mentioned that also on economic issue there is difference between Ambedkar and Gandhiji.( more on this point in later section) Gandhi advocated the concept of – Trusteeship based on private property , harmonious class-relation, in general opposed western civilization including the use of modern machine and method , ( Ambedkar 1946) .Ambedkar on the other hand was against the concept of Trustiship,favoured economy based on common ownership of property at least in agricultural land and key and basic industries in the form of state socialism and is in favour of scientific development.

Ambedakar ,dalits and Indian Marxists

Beside Gandhiji Ambedkar came in close contact with Indian Communist particularly during early 1930s. and the caste and class paradigm of Ambedkar was formed during 1930s in course of confrontation with Indian Marxists. In 1930s Ambedkar worked quite closely with Marxists in Bombay through his own political platform namely Independent Labour Party, however he developed differences and therefore differ on the issue of class-caste paradigm at least on three main points.Before we identify those points it must be mentioned that Ambedkar’s ideas on the economic system were mainly inspired by Marxian framework. In the lecture on Buddha and Karl Marx, Ambedkar observed,

What remains of the Karl Marx is a residue of fire, small but still very important. The residue in my view consists of four items:

(1) The function of philosophy is to reconstruct the world and not to waste its time in explaining the origin of the world.

(2) That there is a conflict of interest between class and class.

(3) That private ownership of property brings power to one class and sorrow to another through exploitation.

(4) That it is necessary for the good of society that the sorrow be removed by the abolition of private property. (Ambedkar 1956)

Thus Ambedkar recognized that there is a class conflict between classes and private ownership of property is the root source of deprivation of the poor masses and that it can be removed by economic reorganization of society on socialistic pattern. Ambedkar thus agreed with ends namely the socialism. However he differed with Marx on the means of realizing the objective of socialism. He advocated democratic means and believed that democratic means are slow but far more enduring ,stable and permanent . This was the first difference with the Indian Marxists.

The second difference was on the question of caste and class interlinkages. .Communists took no note of caste problem during the social reform movement of Ambedkar as they assumed that the explanations of all social problems could be provided in terms of class analysis alone. Ambedkar strongly insisted on the recognition of caste and untouchability as a crucial social reality. He differ with the communists on class-caste paradigm on two main grounds. Ambedkar believed that the caste system involve exploitation and hence argued for undertaking reform of Hindu society as a pre-condition for both political and socialist reform.

On the first question Ambedkar asked as to whether socialists could ignore the problem arising out of the social order. Ambedkar observed.

“They profound that man is an economic creature, and his life is governed by economic facts, that property is the only source of power. They therefore, preach that political reform by equalization of property must have precedence over every other kind of reform.”

Ambedkar argued that economic power is not the only power. That the social and religious status of an individual can also be a source of power and therefore it has to be dealt with.

On second issue Ambedkar emphasized the necessity of undertaking reform of Hindu social order as a precondition for political reform and for socialist reform. Ambedkar raise the question ,namely ,

“Can you have economic reform without first bringing about a reform of the social order?… and argued that… “it is not enough for Marxist to say that I believe in perfect equality in the treatment of various classes. To say that such a belief is enough is to disclose a complete lack of understanding of what is involved in socialism. If socialism is a practical programme and is not merely an ideal, distant and far off, the question for socialist is not whether he believes in equality. The question for him is that whether he minds one class ill-treating and suppressing another as a matter of system, as a matter of principle and thus allow tyranny and oppression to continue to divide one class from another.”(Ambedkar 1936)

In the opinion of Ambedkar Dalit will not join in revolution for equalization of property unless they know that after the revolution is achieved they will be treated equally and that there will be no discrimination of caste and creed. Ambedkar argued

“Mere assurance of Marxist is not good enough – the assurance must be the assurance proceeding from much deeper foundation, namely the mental altitude of compatriots towards one another in their spirit of personal equality and fraternity. Can it be said that the proletariat of India, poor as it is, recognize no distinction except that of rich and poor? Can it be said that the poor in India recognize no distinctions of caste or creed,high and low?If the fact is that they do, what unity of front can be expected from such proletariat in its action against the rich? How can there be a revolution if the proletariat cannot present a united front. Ambedkar further argued that to excite the proletariat to bring about an economic revolution, Karl Marx told them: “you have nothing to lose except your chains.” But the artful way in which the social and religious rights are distributed among the different castes whereby some have more and some have less, make the slogan of Karl Marx quite useless to excite the Hindus against the Caste System. Castes form a graded system of sovereignties, high and low, which are jealous of their status and which know that if a general dissolution came, some of them stand to lose more of their prestige and power than others do. You cannot, therefore, have a general mobilization of the Hindus, to use a military expression, for an attack on the Caste System.

Therefore, in view of Ambedkar the socialist must recognized that the problem of social reform is fundamental even for the participation of Dalits in Socialistic revolution.

Ambedkar put the case for social reform as follows:

But the base is not the building. On the basis of the economic relations a building is erected of religious, social and political institutions. This building has just as much truth (reality) as the base. If we want to change the base, then first the building that has been constructed on it has to be knocked down. In the same way, if we want to change the economic relations of society, then first the existing social, political and other institutions will have to be destroyed.( Gail 1999)

As early as 1936 Ambedkar argued that

“The social order prevalent in India is a matter which Socialist must deal with, that unless he does so he cannot achieve his revolution and that if he does achieve it as a result of good fortune he will have to grapple with it if he wishes to realize his ideal, is a proposition which in my opinion is incontrovertible. He will be compelled to take account of caste after revolution if he does not take account of it before revolution. This is only another way of saying that, turn in any direction you like, caste is the monster that crosses your path. You cannot have political reform, you cannot have economic reform, unless you kill this monster.” (Ambedkar 1936)

The Indian Marxist did not show any concern for the problem of castes during the most part of Ambedkar movement (between the 1920s through 1950s) nor did they provide theoretical explanation for the caste-class paradigm in Indian context. In fact there was no theoretical trend which sought to analyze the interrelation between institution like caste as well as the “material base for caste”. It appeared that this realization came to Engels much earlier.Engel observed.

… According to the materialist conception of history, the ultimately determining element in history is the production and reproduction of real life. More than this neither Marx nor I has ever asserted. Hence if somebody twists this into saying that the economic element is the only determining one he transforms that proposition into a meaningless, abstract, senseless phrase. The economic situation is the basis, but the various elements of the super-structure – political forms of the class struggle and its results, constitutions established by the victorious class after a successful battle, etc., judicial forms, and even the reflexes of all these actual struggles in the brains of the participants, political, juristic, philosophical theories, religious views, and their further development into systems of dogmas – also exercise their influence upon the course of the historical struggles and in many cases preponderate in determining their form. There is an interaction of all these elements in which, amidst all the endless host of accidents, the economic movement finally asserts itself as necessary.

Engel further observed that:

Marx and I are ourselves partly to blame for the fact that the younger people sometimes lay more stress on the economic side than is due to it. We had to emphasize the main principle vis-à-vis our adversaries, who denied it, and had not always the time, the place, or the opportunity to give their due to the other elements involved in the interaction. But when it came to presenting a section of history, that is, to making a practical application, it was a different matter and there no error was permissible. Unfortunately, however, it happens only too often that people think they have fully understood a new theory and can apply it without more ado from the moment they have assimilated its main principles, and even those not always correctly. And I cannot exempt many of the more recent “Marxists” from this reproach, for the most anything rubbish has been produced in this quarter, too…

However, the Indian Marxists ignored this caution and warning of Engels and its application to the Indian situation during most part of the Ambedkars social reform movement between early 1920s to mid 1950s. And even today there are no significant sign or attempt on the part of the Indian Marxists to address the issue of caste even in the Engels framework.

Ambedkar’s Alternative – Constitutional State Socialism with Parliamentary Democracy and Moral revival of Hindu Society through Buddhism

Having recognized the limitations the Gandhism and Marxism in Indian situation Ambedkar developed his approach to the specific situation in India.Ambedkar favoured “ Democratic socialism for economic reorganization of the capitalist economy and Buddhism for social reconstruction or reorganization of Hindu society” . He thus opposed both capitalism and Hindu social organization based on Caste system including Brahmanism and all those elements in Hindu religious philosophy which support directly and indirectly doctrine of inequality and ritualism, fatalism, blind faith ,ignorance and others including Hindu theory of Karma and rebirth which goes against scientific enquiry and temper.

We first discuss the concept of democratic socialism developed by Ambedkar and why? .This is possibly necessary because the concept of socialism as propagated by the democratic socialists, particularly the Indian democratic socialists are varied in nature and lack clarity. Ambedkar’s opposition to capitalism and its alternative in socialism has grown out of his interpretation of democracy. In Ambedkar’s view, the capitalistic system and the parliamentary form of government despite their coexistence for a long time was marked with some painful contradictions. As early as 1943, he observed that “those who are living under the capitalistic form of industrial organization and under the form of political organization called parliamentary democracy must recognize the contradiction of their systems”. The first contradiction concerned the contradiction between the political and the economic system. “In politics, equality, in economics, inequality. One vote, one man one value is our political maxim. Our maxim in economics is a negation of our political maxim. The second contradiction was between fabulous wealth and abject poverty coexisting.

Referring to the first, Ambedkar observed that although parliamentary democracy had progressed by expanding the idea of equality of social and economic opportunity. The hope, however, had not been fulfilled, both on account of wrong ideology. Speaking about ideology, the said that what had adversely affected parliamentary democracy was the idea of “freedom of contract”. This idea had become sanctified and was upheld in the name of liberty. Parliamentary democracy took no notice of economic inequalities and the result of “freedom of contract” on the parties to the contract, if they were unequal. In the name of “freedom of contract”, the strong were given an opportunity to defraud the weak. The result was that the parliamentary system, in claiming to be a protagonist of liberty had continuously added to the economic wrongs of the poor, the downtrodden and disinherited classes.

Also, this ideology did not entertain the possibility that parliamentary democracy might not succeed or that there would be serious discontent if there was no social and economic democracy at its base. Social and economic democracy was the tissues and the fiber of parliamentary democracy. Parliamentary democracy developed a passion only for liberty. But liberty to be real must be accompanied by certain social and economic conditions. First, there had to be social equality. Privileges tilted the balance of social action in favour of their possessors. The more equal the social rights of citizens, the more able they will be to utilize their freedom. Therefore, if liberty was to move to its appointed end, it was important that there should be social equality. In the second, place, there had to be economic security. He wrote:

A man may be free to enter any vocation he may choose… yet if he is deprived of security in employment he becomes prey of mental and physical servitude, incompatible with the very essence of liberty. The perpetual fear of the morrow, its haunting sense of impending disaster, its fitful search of happiness and beauty, which perpetually eludes, shows that without economic security, liberty is not worth having. Men may well be free and yet remain unable to realize the purpose of freedom.

Parliamentary democracy, he wrote, made not even a nodding acquaintance with economic equality. “It failed to realize the significance of equality and did not even endeavour to strike a balance between liberty and equality, with the result that liberty swallowed equality and thus left a progeny of inequalities.

Extending the argument further, Ambedkar observed that in a social economy based on private enterprise and pursuit of personal gain, many people both employed and unemployed had to relinquish their rights in order to gain their living and subject themselves to be governed by a private employer. The assumption in the capitalistic system was that the state should refrain from intervention in private affairs, economic and social, which would result in liberty. Ambedkar observed that ‘but for whom was liberty? To the landlord to raise rent and reduce wages, and for the capitalist to increase hours of work and reduce the rate of wages? It could not be otherwise. For an economic system employing armies of workers producing goods en masse at a regular interval, someone had to make rules so that the worker would work and the wheel of industry would turn. If the state did not do it the private employer would do it, and do it to this advantage.”

To protect the right of the employed as well as unemployed to liberty and to the pursuit of happiness, the most that democratic governments did was to impose arbitrary restraints in the political domain. But such a remedy was of doubtful value. Given that even under adult suffrage all legislatures and governments are controlled by the more powerful, an appeal to the legislature to intervene was a very precarious safeguard against the invasion of the liberty of the less powerful. As an alternative, he suggested limiting not only the power of government to impose arbitrary restraints but also of the more powerful individuals. This was to be done by withdrawing from the more powerful their control over the peoples’ economic life.

Therefore Ambedkar argured that the state had to intervene actively to plan the economic life of people to provide for equitable distribution of wealth. Ambedkar’s proposal was for State ownership in agriculture and a modified form of state socialism in the field of industry and insurance with the remaining economic activities in the private sectors. The state should be obliged to supply the necessary capital for agriculture and industry. Public sector enterprises were to be run most efficiently, with the highest level of productivity possible. Ambedkar was indeed concerned about the efficiency of the public sector institution and therefore emphasized that the efficiency should be the base of state run enterprises. He observed, for example, as regards the structure and nature of the Damodar Valley Corporation:

I am not prepared to accept that the project should be run on non-profitable basis. Nor do I accept that any profit which may accrue after meeting all proper charges shall only be used for reduction of capital expenditure and for betterment of the system. It is impossible to forget the fact that a large part of the misery of the people of the country is entirely due to the inadequate revenue resources of the government. The object of the government business concern is to enable the government to make a profit as any business concern does in order to supplement its resources. I am therefore quite unable to see any justification for ruling out this important purpose from the contribution of Damodar Valley Authority.

Ambedkar saw no alternative to democracy and therefore firmly believed in it as an appropriate form of political organization, but at the same time he emphasized the need to strengthen the social and economic foundation, which he saw as the tissues and fibres of political democracy by making the socialism as part of the constitution .So his concept of state socialism is “constitution state socialism with parliamentary democracy.” He, therefore, advocated a political-economic framework namely constitutional state socialism with parliamentary democracy so that the social and economic organization would be more egalitarian and consequently, the political means would become more meaningful to the poor and underprivileged.

Alternative to Hindu Social and Religious Order

Ambedkar recognized and emphasized the need for social reforms and reorganization along with the economic reforms of Hindu social order for he believe that economic equalization may not change the exploitative social based of the caste system although it may reduce in intensity. So he sees a great necessity to have social reform movement. On this issue Ambedkar in-depth analysis of Hindu social and religious order lead to the firm conclusion that root of untouchability and discrimination lies in social and material based of the Hindu social and religious order. Ambedkar believe that

“Hindu observed untouchability and caste not because they are inhuman or wrong headed.” They observed caste because they are deeply religious. People are not wrong in observing caste. In his view… what is wrong is their religion which has inculcated this notion of caste. If this is correct then obviously the enemy, you must grapple with, is not the people who observed caste, but the Shashtras which teaches them this religion of caste. Criticizing and rediculizing people… is a futile method of achieving the desired end. The real remedy is to destroy the belief in the sanctity of Shashtras… how do you except to succeed, if you allow the Shashtras to continue to mould the belief and the opinion of the people… Reformer working for removal of untouchability… do not seems to realize that the act of the people are merely the result of their belief inculcated upon their mind by the Shashtras and the people will not change their conduct until they cease to believe in the sanctity of the Shashtras on which their conduct is founded.

Ambedkar therefore suggested that

To agitate for and to organize inter caste dinners and inter caste marriages is like forced feeding bought about by artificial means. Make every man and woman free from the thralldom to the Shashtras, cleanse their minds of the pernicious notions founded on the Shashtras, and he or she will inter dine and inter marry, without your telling him or her to do so.

In Ambedkar’s view real remedy is to replace the social relations governed by the caste system to be replaced by the one based on equality, justice and fraternity. It is in this context Ambedkar favoured the social philosophy of Buddha which he thought will help to restructure the social, cultural, political and economic relations to promote equality, justice and fraternity.

Ambedkar’s influence on Indian policy toward dalits

Based on this perspective of Hindu social order (and its adverse consequences on dalits), right from the early 1930’s Ambedkar advocated specific policies to over come the cumulative and multiple deprivation of dalits. The present approach adopted by the government toward the dalits was indeed the contribution of Ambedkar. Ambedkar had argued with the British and the latter with the Congress that the problem of dalit is an unique and different from rest of the poor .It is unique in the sense that dalits are the only group which suffered from exclusion and isolation from all possible means of living and sources of income ( such as land ,capital ,employment ,education ) and also civil, cultural /religious and political rights. The high caste person effects the exclusion and isolation through the machanism of discrimination. The discrimination in all walks of life and restriction on participation in the general process of social and economic development is the main obstacle for the development of dalits. And there fore in addition to the systemic changes (in term of socialistic economy, economic planning , and active role and participation of the state in economic and social governance) ,Ambedkar also favored Reservation policy as an instrument of protecting the dalits from discrimination and ensuring their participation in various spheres of life .Indeed it goes to the credit of Ambedkar that he was able to develop this concept of Reservation or Affirmative action to provide equal participation to the discriminated groups. The policy toward the dalits and even other deprived groups such as tribal and other backward classes during the pre- independence and after was not only conceived by Ambedkar but he was indeed the pioneer and architect of this policy much before it was accepted in many other countries of the world.

The policy of reservation in politic, education , public services and protection for civil and cultural rights in favour of dalits had originated in the early 1930’s in the formulation of the 1935 Act before independent. After the independent in recognition of their unique problem the Indian constitution made special legal provision in 1950 against the practice of discrimination and exclusion and also devised policies to improve their access to social, economic and political rights. In the social spheres two anti-discrimination Acts namely Anti-untouchability Act of 1955 ( later in 1979 renamed as Civil Right Act) and Prevention of Atrocities against Schedule caste Act 1986 were passed.

In the economic spheres there are no specific anti-discriminatory laws, but to protect them from the discrimination the government has developed what is called “Reservation Policy” under which due share in the government jobs , educational institutions and other spheres is ensured in proportion to their population . Additionally in mid 1970’s as a part of Five Year Economic Plan, the government also developed a sub plan named as ‘Special Component Plan for the Schedule Caste” with a purpose to improve their access to employment ,capital ,education and social amenities like housing and canalize the financial resource for the special programmes for their social and economic development.

Thus the ‘anti discriminatory laws’ and “Reservation policy” are two specific policy instruments, which have been used by the government to provide social protection against discrimination and exclusion and to improve the access of the schedule caste (SC) to sources of income and basic service like education, housing etc.

Dalit after Independence-Economic and social change

These special policy instruments along with the general development has brought some improvements in the economic and educational situation of the scheduled caste since the early fifties. There has been some improvement in the ownership of agricultural land and other capital assets , as close to one third of the SC households now are engaged as self employed farmer and business households . The participation in regular/salaried jobs particularly in urban area has also improved .As result of improved access to capital assets and regular/salaried jobs the magnitude of poverty has also reduced from two-third in the early 1950’s to about half in the early 1990’s.There has been a progress in education level. This small but important gains have to be seen in context of traditional customary restrictions on the ownerships of capital assets and basic service like education under the caste system and the institution of untouchability

However despite this positive change the schedule caste still lag far too behind the other groups in Indian society and suffered from high degree of economic deprivation and vulnerability. In the rural area (where three-fourth of SC live) over seventy percent of the SC household still don’t have minimum access to (agricultural) land and non land capital assets and as result over 65% of them are wage labour house holds. In labour market however they suffered from high rate of unemployment and low wage rate. The unemployment rate among the schedule caste is two time higher than other groups and the wage rate also tend to be low as compared with other group, as results of which their yearly wage income is low and there fore magnitude of poverty is high. In the early 1990’s about half of them were poor as against only one fourth among other section. Poverty among the wage labour household was more than sixty percent. The self employed household being engaged in patty business also suffered from high poverty. Thus caste based economic inequality in access to sources of income like capital assets ,employment, education and in the end in poverty between the Schedule caste and rest of the section continued to be high despite some positive change.

Economic Deprivation

In this section therefore we present the changes in the economic and social situation and the nature of economic deprivation and discrimination. How far do the traditional customary restrictions related to ownership of sources of income imposed on the low-caste untouchable continue? Has their access to agricultural land and capital in rural and urban area improved? We have selected data on the comparative situation of the Scheduled Castes (SC) and others in rural and urban areas for the recent years, in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Some sources also go back to the 1960s, the 1970s and to the 1980s.

Disparities in Access to Ownership of Agricultural Land and Capital

About three-fourths of the SCs live in rural areas, where the main sources of income are either cultivation of agricultural land, wage labour or some kind of non-farm self-employment. Access to agricultural land for cultivation and capital for undertaking non-farm self-employment is critical. In 1993-94 only 19.12 per cent of all SC households cultivated land as (independent) self-employment worker whereas among the Other (i.e. non SC/ST) the percentage was more than double, 42.12 per cent (Table 1). The percentage of those employed in some kind of non-farm self-employment activities was 10.32 per cent and 13.89 per cent respectively for SC and Others. Taking both farm and (rural) non-farm self-employment, only 23.49 per cent of SC household seem to be engaged in self-employment activities as compared to 56.31 per cent for others, in rural area.

In urban areas the disparity in the access to capital is well reflected in the lower proportion of self-employed workers among the Scheduled Caste. By 1993-94 only 24.08 per cent of total SC urban households were self-employed, as compared to 35.05 per cent for Others. The lower proportion of SC as self-employed in agriculture, in non-farm sector in rural area and in urban area as compared to others, revealed the continuation of lack of access to SCs to ownership of agricultural land and capital. The limited access to agricultural land and capital assets is both due to the historical legacy associated with the restrictions of caste system to require means of income by the untouchables and ongoing discrimination in land market and capital market and other related economic spheres.

Inadequate access to agricultural land and capital (for self-employment activities) leaves no option to SC workers except to resort to unskilled manual wage labour, consequently it leads to enormously high level of (manual) wage labour among the SCs. In 1993-94 the proportion of agricultural wage labour was about 50 per cent as compared to 22 per cent among others. Taking both agricultural and non-agricultural labour in rural areas, the percentages of wage labour reached 60 per cent as compared to 29 per cent for others. In urban areas also disparities in the incidence of wage labour are evident. The proportion of casual labour among the SCs was 27 per cent as against only 10 per cent among the others.

Differences in the proportion of regular wage earner and salaried persons between SCs and others was minimal in urban areas. In the rural areas, the proportion of such workers was lower among the SC (5.8 per cent) as compared to others (9.2 per cent).

Disparities in Employment

Since more than 60 per cent of the SC workers in rural areas and more than 30 per cent in urban areas depend on wage employment, their earnings are determined by the level of employment and wage rates. The SC worker seems to suffer from possible discrimination in employment. Table 2 shows the unemployment rate of the SC vis-à-vis the others for 1977-78, 1983, 1987-88 and 1993-94. The unemployment rate of SCs are much higher than that of other workers based on current weekly and current daily status. In 1977-78, 1983-84 and 1993-94 the unemployment rates based on daily status for SC male workers were at 6.73 per cent, 7.16 per cent and 4.30 respectively, significantly higher than 3.90 per cent, 4.03 per cent and 2.70 for others. A similar gap exists for female labour too. The unemployment rate for SC females on daily status basis was 1.90 in 1977-87, 2.16 per cent in 1983, and 2.00 1993-94 which was again higher than the 0.97 per cent, 0.91 and 1.10 per cent respectively for other females. The higher unemployment rate based on current weekly status and current daily status clearly shows that under-employment among SC workers is much higher than among other workers.

Higher unemployment rate of SC worker (which is twice that of others) indicates a possible existence of caste-based discrimination against SC workers in hiring. As we shall see later, micro-level studies revealed some evidence of discrimination against SCs in occupation, employment, wages and others.

High Poverty

With higher incidence of wage labour associated with high rate of under-employment the SCs would suffer from low income and consumption and a resultant greater level of poverty.

This is reflected in the proportion of persons falling below a critical minimum level of consumption expenditure, what is called the poverty line. Table 3 presents the poverty ratio for SCs and others for 1987-88 and 1993-94 at the all-India level. In 1993-94 about 48.00 of SC household were below the poverty line in rural areas as compared to 31.29 per cent for the general population. The poverty level among the SCs was thus high compared to others. What is striking is the variation in poverty ratio across household types. The incidence of poverty was about 60 per cent among agricultural labour followed by 41.44 per cent among non-agricultural labour. The level was relatively low for persons engaged in self-employed activities in agriculture (37.71 per cent) and in the non-agricultural sector ( 38.19 per cent). For each of these household types, however, the proportion of SC household was much higher than their counterparts among the non-SC/ST group.

In urban areas about 50 per cent of the SCs were below the poverty line in 1993-94, as compared to 29.66 per cent among the Others. Further, the incidence was astonishingly high among the casual labour (69.48 per cent). The disparities in the level of urban poverty between the two social groups were relatively higher in the case of self-employment and regular salaried and wage workers but less in the case of casual labour.

This indicates that by the early 1990s still half of the SC population was below the poverty line both in rural and urban areas. The incidence of poverty was astonishingly high among wage labour households in rural and urban areas, who constitute about 60 per cent of the workforce in the rural area and 30 per cent in urban areas. The 1993-94 figures revealed that the SCs were at least twenty-five years behind the other group in terms of level of poverty.

This macro-level comparative account of the economic position of the formerly untouchable and upper-caste persons covering relevant economic indicators provides convincing evidence of the continuing economic inequalities associated with caste. It is thus beyond doubt that the historical impact of traditional caste-based restrictions on the ownership of property, employment and occupation are still visible in significant measure, the access of the formerly untouchables to income-earning capital assets and employment is limited, and their segregation into manual labour is overwhelmingly high. The two prime economic attributes of the caste system thus seem to be present in sizeable measure, even today.

Economic discrimination

Due to the absence of legal protection against the economic discrimination very few empirical studies have tried to understand the phenomenon of economic discrimination. However few studies revealed the practice of discrimination in various economic spheres against the untouchable and violation of human rights with respect to economic rights. Banerjee and Knight (1991), Deshi and Singh (1995) have brought out the significant presence of caste and untouchability-based economic discrimination in urban job market. Banerjee and Knight in their study of the Delhi urban job market during 1975-76 observed that “use of the standard methodology showed that there is indeed discrimination by caste”, particularly job discrimination through the estimation of occupational attainment function and it is quantitatively more important. They further observed that “Discrimination appears to operate at least in part through traditional mechanism, with untouchables disproportionately represented in poorly-paid” dead-end jobs.

The discriminators are likely to be other workers and employers. Even if discrimination is no longer practised, the effects of past discrimination could carry over to the present, for instance in the choice of occupation. This may help explain why discrimination is greatest in operative jobs, in which contracts are more important for recruitment, and not in white-collar jobs, recruitment to which involves formal methods. The economic function which the system performs for favoured castes suggests that “taste for discrimination is based, consciously, or unconsciously, on economic interest, so making prejudice more difficult to eradicate”. The study by Dhesi and Singh (1959) of Delhi on education, labour market distortions and relative earning differences across religion-caste categories in 1971 also observed “differences in jobs associated with education and labour market distortion arising out of caste and religious background of persons”.

Among the micro-level studies considered earlier, the studies on Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka also provide micro-level evidence about economic discrimination in occupation, employment, wages and loan and other economic spheres. The study on Andhra Pradesh (Venkateswarlu, D., 1990) indicates that when untouchables wanted to switch over from their traditional occupation in the rural area to some other occupation, they were abused or beaten. The Karnataka study (Khan, Mumtaz Ali, 1995) revealed that nearly 85 per cent of the respondents continue with their traditional occupation and only 15 per cent could make a switch. In the urban areas, however, 56 per cent expressed a shift in the traditional occupation.

The Orissa study (Tripathy, R.B., 1994) for 1987-88 observed discrimination in a few economic spheres. Nearly 96 per cent of respondents in one village and all the formerly untouchable respondents in the second village were discriminated against in wage payment. 28 per cent in one village and 20 per cent in another faced discrimination in the share of rent. Discrimination in interest rate changed by the moneylender was found in both villages.

Untouchability, and Atrocities

We now present empirical evidence on the violation of civic, political, economic and religious rights, with respect to low caste untouchable, first we present the macro-level (i.e. all India) evidence and then discuss the evidence from the selected regions in the country based on primary survey by individual scholars.

All India Picture :

Table 4 presents the incidence of civil rights violations of former untouchables between 1955 and 1997. The violation of civil rights include prohibition to untouchable to use public water bodies such as well, tape, temple, Tea stall, Restaurant, community Bath, road, and other services. It is seen from the table that at the all-India level, the average number of cases of human right violation of untouchable registered annually were 480 during the 1950s, 1903 during the 1960s, 3240 during the 1970s and 3875 during the 1980s and 1672 during 1990’s. Table 5, also shows that on an average 30,000 cases of general crimes and atrocities were committed on the former untouchables annually during 1981-97. During 1981-86 and 1995-97 (i.e. nine years) a total of 269,000 cases of crime and atrocities were committed against the former untouchables. The break-up of the atrocities for the year 1997 shows 504 cases of murder, 3462 of grievous hurt, 384 of arson and 1002 cases of rape, and 12149 cases of other offences. The data between 1981 and 1997 showed that on an average annually about 508 formerly untouchable persons were murdered, about 2343 were hurt, 847 were subjected to arson, 754 women were raped and about 12,000 were subjected to other offences. With 513 murdered every year we cannot say that the formerly untouchable persons enjoy an unequivocal right to life. With 847 cases of arson annually, we cannot say that they have the right to safe and secure life. With about 750 cases of rape annually we cannot say that Scheduled Caste women have the assurance of a safe, secure and dignified life. And with 3,000 cases of civil rights violation annually we cannot say that the Scheduled Castes enjoy liberty and equality in civic and political sphere.

Regional Evidence –Primary studies

Generally, registered cases of this nature are severe (and often public) and it requires courage from the victims or encouragement from NGOs or others to register the case. The undercurrent of untouchability and humiliation, which is part of the general social relation and qualitative in nature, forms a part of their day-to-day experience but remains unreported.

The studies based on primary surveys, however, reveal the actual magnitude of the problem. From the massive literature on the practice of untouchability and atrocities, only a few are presented here. These include a study on Karnataka (1973-74 and 1991), Andhra Pradesh (1977), Orissa (1987-88) and Gujarat (1971 and 1996). Karnataka and Andhra are in southern India, Orissa in eastern India and Gujarat in western India.

Karnataka Study, 1973-74. The Karnataka study for 1973-74 is based on a fairly large sample of 76 villages, 38 urban centres and 3330 households. (Table 6) Of the total households 73 per cent were former untouchables (Parvathamma 1984). The study captures the incidence of untouchability in social, religious and economic spheres of societal relationship, such as drawing water from the common well, entry to the village temple, access to upper caste locality, entry into the village shop and tea-stalls, access to the services of barber, washerman, priest, tailor, blacksmith, village and government doctor and nurse, milling the grain and so forth, services of school, post-office, health and village panchayat institutions. The study came up with the following evidence.

(a) Nearly 54 per cent of the formerly untouchable respondents were not allowed to draw water from the public well in the village and another 6.4 per cent faced 0discrimination of various types. The magnitude of the problem was much less severe in urban centres, but even in urban areas 15 per cent of the respondents were not allowed to draw water from public water sources and another 4.6 per cent faced discrimination of various kinds. (b) The practice of untouchability was far more widespread in the access to temple as nearly 60 per cent were denied access to the village temple. (c) The access to high-caste houses was limited, as 63 per cent of the former untouchables could not enter them. (d) The practice of untouchability was less in public utilities places like the tea-shop and grocery shop. In grocery shops about 11 per cent of the respondents were not allowed inside while another 11 per cent faced discrimination in access to village shops. In the local village tea-shop, 43 per cent of the formerly untouchable were not allowed free access. In the urban area 94 per cent had easy access, but 10.5 per cent faced one or another kind of discrimination. (e) As regards religious places, 71 per cent of respondents were refused service by Hindu priests. (f) In essential services, the practice of untouchability was widespread. About 53.0 per cent of the respondents did not receive the services of a barber and washerman in the village. In urban areas the access has improved considerably. Most of the respondents, however, had non-discriminatory access to the service of tailors. (g) In public services like post-office, health, education and others the practice of untouchability was much less. As much as 98 per cent had access to postal services, but 49 per cent faced some kind of discrimination, in so far as postmen avoid entering the residential areas of former untouchables, opting to hand over the mail to a formerly untouchable person of the locality for distribution. (h) Generally, discrimination in the service rendered by the government doctor and nurse and village doctor and the village school was less. (i) About 13 per cent of the rural untouchable respondents cannot wear clothes of their choice or ornaments even today.

Karnataka Study, 1992-93. Nearly twenty years later another study was conducted in Karnataka by taking 941 respondents from 52 villages and from most of the districts(Mumtaz Khan 1995). The study came up with the results that except in political activities, in all other areas of social interaction, untouchability was practised in a vast majority of the cases (see Table 7)

- For 80 per cent of the respondents entry to village hotels was still barred. b. 70 per cent of the respondents were denied entry into the village temple and another 70 per cent were denied participation in religious processions. c. In most cases there was no free access to high-caste water taps. Another 68 per cent had no access to the village water tank. d. 70 per cent of the respondents said that social mixing or relations were not allowed. e. In the political sphere (i.e. sitting together or taking tea in the village panchayat office) the discrimination was much less.

It will be seen from a comparison of Tables 2 and 3 that between 1973-74 and 1992-93 some change has occurred. The practice of untouchability was relatively less in the political sphere but its magnitude was still very high in access to the village temple, religious community events, hotel, high-caste water (public) taps, water (public) tank and interpersonal social relations.

Andhra Study, 1977. The third study is for Andhra state which adjoins Karnataka. This study was conducted in 1977 and covered a sample of 396 respondents (of which 196 were formerly untouchable) from six villages (Venkateswarlu 1990). The study disclosed the following results (see Table 8).

- Most untouchables felt that the temples were still barred to them. b. Most of the respondents said that they were not allowed to enter the houses of caste Hindus. c. Marriage procession through the public village road by untouchables is prohibited on one pretext or another. d. There is no access to public drinking water source. The well or tap is located in the high-caste locality and attempts by the former untouchables invites objection and physical obstruction. e. The majority of the untouchable respondents reported being beaten by the upper castes, ranging from frequently to rarely. Raids on untouchable hamlets or houses, sometimes followed by looting, were reported. Violence was also perpetrated in the form of kidnapping, insults, rape, physical torture and threat or attempt to murder. f. Many formerly untouchable respondents were prevented from exercising their franchise in elections. In some cases they were also prevented from participating in political activities like organizing meetings in the village or taking an independent position on political issues, or contesting elections.

Orissa Study, 1987¬-88. The study in Orissa state was conducted in 1987-88 and covered two villages (one small and one large) and 65 formerly untouchable respondents (heads of households) (Tripathy 1994). (Table 9) The study came up with following observations:

- An overwhelming majority, i.e. 80 per cent of respondents in the small village and 70 per cent in the big village were prohibited from drinking water from the public open well and public tube well. In the big village there were separate pulleys in wells for the untouchables.

b. 3 per cent of respondents in the big village and 90 per cent in the small village observed that while locating public wells/tube wells the untouchables’ convenience was not taken into account.

c. In village community feasts and marriage in both villages the former untouchables were treated unequally. The same is the case with regard to temple worship, barber service, washerman services, priest services, etc. 64 per cent in the big village and all in the small village were treated unequally in the village meeting. 80 per cent of the respondents in both villages did not have access to tea-shops; 70 per cent in the big village and 80 per cent in the small village faced unequal treatment or discrimination in getting services from the grocery shops.

d. Most of the former untouchables in both villages have free access to school and hospitals.

e. About 80 per cent in the small village and all in the big village faced discrimination in village cultural events (i.e. drama) and village festivals.

f. In both villages the settlement of untouchables is separated from that of the upper castes.

g. Their small number, poverty and fear (in the small village) discourage the former untouchables from contesting in elections. Numerical strength, better economic status and political consciousness encourage contesting in election and participation in the political process.

Gujarat Study. The study in Gujarat, conducted in 1971, is based on a survey of 69 villages. A repeat survey of these villages was done in 1996 to see changes in practice of untouchability (Desai 1976; Shah 1998). (Table 10) To what extent and in which sphere has untouchability been abolished and in which spheres is it observed? The first study looks into the practice of untouchability in seventeen spheres of village life, which include the private and public domain. The public domain is divided in two spheres. One is those institutions and places which are managed through funds provided by the state and/or local community from common resources like land, forest, pond and river. The other sphere of public life is managed by the market in which the relationship is contractual of buying and selling commodities and/or services, panchayat, common source of water and temple. The latter includes shops selling goods, services such as hair-cutting, tailoring and paying wages. The private sphere is confined to allowing members of Scheduled Caste (SC) inside one’s house without discrimination. There are some quasi-public spheres which involve personal preference in public places.

The practice of untouchability in sitting arrangement of the students in village schools was negligible in 1971; it had disappeared in 1996. SC and non-SC students intermingle in the school freely. However their friendship in many villages does not extend after the school hours. Non-SC teachers do not discriminate against SC students but they are not easily accessible to SC students outside the school boundary. Not all the schools have the facility of drinking water for students. Where it exists, all students take water from the common vessel.

Nearly 10 per cent of the village schools have teachers belonging to SCs. None of them complained that their colleagues discriminate against them in school. However except in south Gujarat, these teachers do not get accommodation in the high-caste locality of the village. They either commute from their village or from the nearby town or they rent a house from the SC locality.

Almost all villages are covered by state transport. Except in 7 per cent of the villages, untouchability is not observed while boarding and sitting in the bus. Crude discrimination against SC is observed in one per cent of the villages, where he/she is almost denied the right to sit with an upper-caste person. In the remaining 6 per cent of the villages, untouchability is practised in a nebulous form. That is, a member of the SC is expected to stand up and offer his/her seat to a high caste passenger; or the latter is allowed to board the bus first.

The 1971 study found that there were certain restrictions on the free movement of the SCs on some roads in as many as 60 per cent of the villages. Their number has declined considerably. Yet the SCs encounter some restrictions on their movement in 23 per cent of the villages. As such there is no ban on the SCs using certain village roads. But they do become victims of wrath varying from abuse to even physical assault if they enter the streets of the upper castes. They have to stop and give way to members of the upper castes, particularly brahmins and rajputs in general and elderly persons of the dominant upper castes in particular.

Even in villages where the SCs do not face restriction in their day-to-day movements, they are subjected to mortifying comments by members of the upper castes about their former untouchable status.

Most of the village post-offices and postmen do not practise untouchability while giving stamps and taking money as well as delivering mail. The postmen go to the SC localities and hand over the mail to the addressee. But postal employees observe untouchability in 8 to 9 per cent villages. They do not give postal stationery and mail in the hand of the SC addressee. There has been a slight decline in the practice of untouchability during the last twenty years in delivering mail, but in the selling of stamps the proportion of villages practising untouchability has increased. The postal employees observe untouchability in 8 per cent of the villages.

Open or subtle untouchability is practised in panchayat meetings in 30 per cent of the villages, as against 47 per cent in 1971. The sitting arrangement in panchayat offices is common for all the members, but there is a tacit convention whereby certain seats are marked for SC members. Though tea and snacks are served to everyone, separate plates and cups are reserved for SC members, and stored separately. In the past SC members had to wash their used utensils, but no longer.

In most village temples, 75 per cent SCs are not allowed to enter beyond the threshold, though they may worship from a distance. One temple may be open for the SCs and another temple restricted from their entry. The SCs in many villages where their numbers are large, have constructed temples in their localities to avoid confrontation.

In 1971, 44 villages had separate water facility for the SCs near their localities. Two villages had been added to this list in twenty-five years. Untouchability is not experienced in normal times, but when water is scarce, the SCs experience difficulty and discrimination in taking water from high-caste localities. In the remaining 23 villages in which the untouchables take water from the common source, untouchability is practised in 61 per cent of the villages. In most such villages SC women take water after the upper-caste women, or their tap or position on the well is separately marked. In seven villages (11 per cent of the sample villages) the SC women are not allowed to fetch water from the well. They have to wait till the upper caste women pour water into their pots. The SC women are constantly humiliated by the upper-caste women who shout at them: “Keep distance, do not pollute us!”

The practice of untouchability has strikingly declined in occupational activities, i.e. in buying and selling commodities. In 1971, in as many as 85 per cent of the villages SC members were barred from entering shops; now in 1996 shops in only 30 per cent villages are so restricted. Similarly the practice of untouchability in giving things and receiving money has been reduced from 67 per cent to 28 per cent.

The status of being formerly untouchable comes in the way of potential SC entrepreneurs. They fear that upper-caste members would not buy from their shop or would harass them. In a village in Ahmedabad a SC autorickshaw driver who asked for the fare from a sarpanch belonging to a middle caste was severely beaten. This is not a rare case, and such upper-caste attitude inhibits SC enterprise.

Most tailors do not practise untouchability. They touch the SC client to take measurement. However, in most cases they do not repair used clothes of the SCs. Nearly one-third of the potters observe untouchability while selling pots to SC clients. Most of the barbers (nearly 70 per cent) refuse their service to SC males. Muslim barbers do not practise untouchability. The traditional patron-client relationship still continues, though the client pays in cash for the service. A few barbers in large villages have set up shops. Many do not mind serving a SC client, but some do.

The extent of untouchability has remained almost intact in the sphere of house entry. Except a few villages, SC members of village society do not get entry beyond the outer room of the high caste. Even in villages where the young folk do not believe in physical untouchability, and who serve tea to SC guests in their houses, entry in the dining room is not encouraged.

The practice of untouchability has been considerably reduced in some of the public spheres which are directly managed by the state laws and which have a relatively non-traditional character like school, postal services and elected panchayats. The number of villages observing untouchability on public roads, restricting free movement of the SCs has considerably declined from 60 per cent in 1971 to 23 per cent in 1996, but it is too early to say that the untouchable is not discriminated against in the public sphere. As many as 30 per cent of the village panchayats still observe open or subtle discrimination with their elected members belonging to SCs.

This macro and micro-level (i.e. based on primary survey) empirical evidence presented above shows the magnitude and the nature of continuing practice of untouchability or human right violations against the untouchables, even after fifty years of India’s secular constitution and enactment of the Civil Rights Act in 1955. The practice of untouchability and resultant discrimination has reduced in the public sphere like panchayat offices, schools, use of the public road, public transport, health and medical services, services of shops (for buying of goods) and services rendered by the tailor, barber, eating-places and tea-shops in large villages and urban areas. But even here discrimination in various subtle forms prevails. In several other spheres, the practice of untouchability and discrimination is fairly widespread. All the micro-level studies show that the settlements of the untouchables are away from the high-caste locality, endogamy (which is the backbone of the caste system) continues, entry to the former untouchables in private houses and temples is limited, and interdining or common sharing of tea and food is extremely limited. Pressures and restrictions on voting and political participation also prevail. The restriction on the change of occupation and discrimination in employment, wage rate, share of rent, rate of interest charged and sale of items from shops owned by the untouchables are fairly widespread in the rural areas, where three-fourths of the former untouchables live.

Why discrimination and violence?

The official data and the studies by individual researcher indicate that the behavior of the high caste towards the untouchable is still influenced by the traditional code of caste system .Why do the higher caste persons continued to practice untouchability, and discrimination despite the provision in the law to the contrary? And why do they resort to physical and similar forms of violence against the untouchables when the latter tries to gain a lawful access to human rights and equal participation in social, political, cultural, religious and economic sphere of community life? The reasons for both are rooted in continuing faith of the high caste Hindus in the sanctity of institution of case system and untouchability and more importantly the fear of loosing the immense social and economic( or material ) privileges associated with the preservation of the system. In this respect Ambedkar observes

Why is it that large majority of Hindus do not inter-dine and do not inter-marry? There can be only one answer to this question and it is that inter-dining and inter-marriage are repugnant to the beliefs and dogmas which the Hindus regard as sacred. —- Caste may lead to conduct so gross as to be called man’s inhumanity to man. All the same, it must be recognized that the Hindus observe Caste not because they are inhuman or wrong headed. They observe Caste because they are deeply religious. People are not wrong in observing Caste. in my view, what is wrong is their religion, which has inculcated this notion of Caste. (Ambedkar 1936)

Thus in Ambedkar’s view the caste system received philosophical support and justification from the Hindu religion and it is this which provide abiding strength for its continuation . Also it is this faith in the system which induce the high caste for its continuation The significant point however is about the role of religious, social, philosophical elements in Hinduism which provided divine justification for the origin and sustenance of the Hindu Social System. Deepak Lal also recognised the negative role of Hindu religion, he observed “Aobviously the religious, philosophical and ritual elements in Hinduism are equally (if not more) important in perpetuating the system…”and added that” the relative privacy of one or other factor in originating or perpetuating the system is not of importance for my purpose. What is important is that the economic and non-economic aspects of the system mutually reinforced each other@. (Deepak Lal, 1989, p. 73)”. Ambedkar located the role of religious ideology of Hinduism in providing divine support and justification to the doctrine of inequality in all spheres. While commenting on the centrality of the Hinduism Ambedkar observed ,

“religious ideals as a form of divine governance for human society falls into two classes, one in which Society is the centre and the other in which the Individual is the Centre, and for the former the appropriate test of what is good and what is right i.e. text of moral order is utility while for the latter the test is justice. Now the reason why the philosophy of Hinduism does not answer the test either of utility or of justice is because the religious ideal of Hinduism for devine governance of human society is an ideal which falls into a separate class by itself. It is an ideal in which the individual is not the centre. The centre of the ideal is neither individual nor society. It is a class; it is a class of supermen called Brahmins. Those who will bear the dominant and devastating fact in mind will understand why philosophy of Hinduism is not founded on individual justice or social utility. The philosophy of Hinduism is founded on totally different principles. To the question what is right and what is good the answer which the philosophy of Hinduism gives is remarkable. It holds that to be right and good the act must serve the interest of a class of supermen, namely the Brahmins. Any thing which serve the interest of this class is alone entitled to be called good (Ambedkar first published 1987, page-72).

This in Ambedkar’s view is the core and the heart of the philosophy of Hinduism. It teaches that what is right for a one particular class is only thing which is called morally right and morally good. It is also important to recognized that in Hinduism there is no difference between legal philosophy (or law) and moral philosophy (morality), that is because in Hinduism there is no distinction between legal and moral, legal being is also moral being. Further morality in Hinduism is also social and both are concerned with interest and privileges of one class.

The faith in the system is not for spiritual and cultural reasons alone but more so for material reasons because it provide immense social and economic privilege to the high caste persons .It is this which induce them to maintain the system.However although immense privileges associated with the system induce them to retain the system at any cost but it may not necessarily enable or permit them to enforce it . This is dependent on other enabling factors. This brings us to the question of use of violence by the high caste against the untouchables. It must be mentioned that the Hindu social order also provides for religiously sanction mechanism of social ostracism or system of penalties to maintain the system This include several painful physical punishments beside the social and economic boycott. Therefore if the large majority of Hindus are found to be using violent method against the untouchables , the reason is to be found in the belief and the faith in method prescribed in the traditional caste system. But what enable them to do so is the economic and demographic power against which the dalit find themselves completely helpless. Some of the studies on atrocities and violence bring out this thing quite clearly. The Commissioner for scheduled caste and scheduled tribes in one of their study observed :

“Some of the major causes of atrocities and other offences against Scheduled Castes are related to issues of land and property, access to water, wage payments, indebtedness and bonded or forced labour. Issues of human dignity, including compulsion to perform distasteful tasks traditionally forced on Scheduled Castes, and molestation and exploitation of dalit women are also involved. Caste related tension is exacerbated by economic factors, which contribute to violence. It is the assertion of their rights, be they economic, social or political, by the Scheduled Castes and their development, which often invite the wrath of the vested interests. Disputes during elections, animosity due to reservation, jealousy due to increasing economic prosperity, violence related to the process of taking possession and retaining Government allotted land, tension due to refusal of SCs to perform tasks such as disposal of dead cattle or cutting umbilical cord, are manifestations of the resentment of the high caste against increasing awareness among Scheduled Castes, assertion and prosperity among the SCs. Like land, water is another sensitive issue. Accessibility of drinking water and water for irrigation and disposal of water removed from water logged areas become issues that can trigger off atrocities on SCs. Castiest fervor during religious and social ceremonies, disputes arising during sowing and harvesting operations, and removal of crops from the granary after harvesting, have also been known to cause tension. Increasing awareness and empowerment of SCs, manifested in resistance to suppression, also result in clashes”. (The Report of the commission for SC/ST of 1990).

Concluding Remarks